Have you ever been convinced that you couldn’t do something, that in fact you could? Have you ever believed that a loved one thought something about you, only to find out later that they held the opposite view? Have you ever been convinced something would work, and then discover that only you’d missed some crucial detail? In all those cases, you’ve been deceived by your mind that had sold you a bill of goods about how you, other people and the world worked. In the language of ACT, you were a victim of cognitive fusion.

Once our minds have learned language (which would seem to be a learned rather than an innate ability), they never stop stringing words and experiences together to produce thoughts, stories, interpretations and opinions. These are so vivid and convincing that we spend a good 90% of our lives “in our heads,” paying more attention to our mind’s never-ending stream of stories than with to present moment and our immediate surroundings. Only humans do this. It’s as if words and stories became welded to our experience of the world, as if we were forever seeing the present through the thought-tinted glasses of our talking minds. And these stories can play tricks on us and get us tuck. Buddhists don’t call it the monkey mind for nothing.

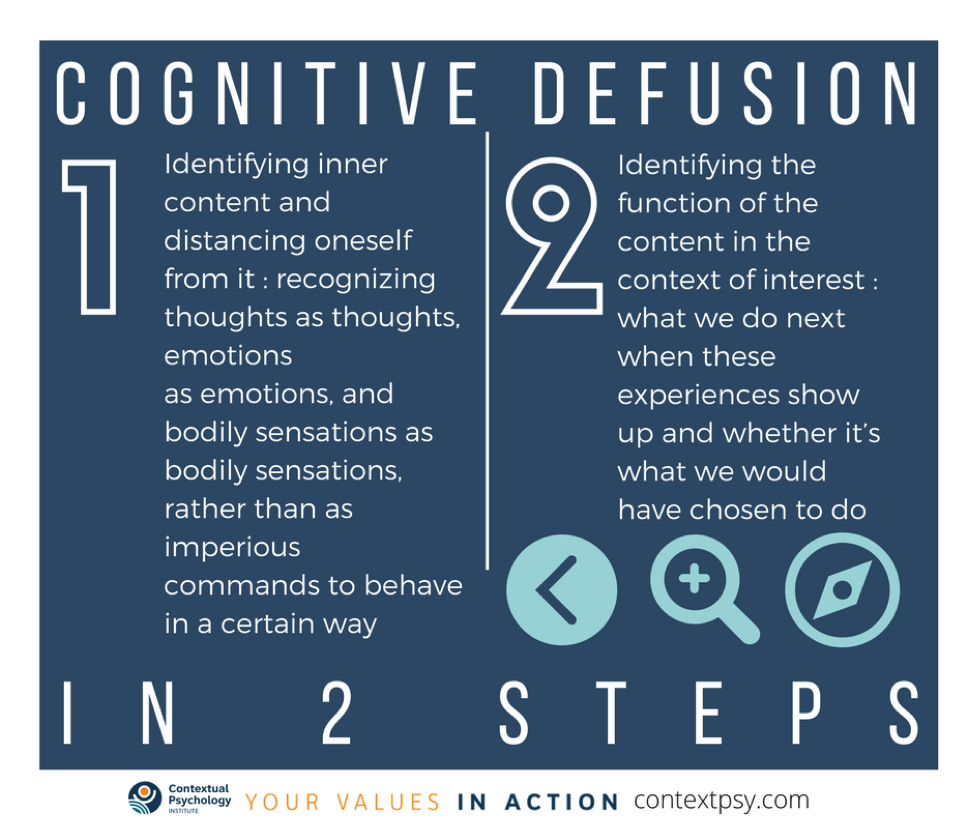

To help us gain some wiggle room, ACT suggests cultivating cognitive defusion. This is a metaphorical term to help us unsolder the stories that can so easily get fused with our experiencing of the world. Distancing from the content of our mental productions is not new or unique to ACT. It hails back from ancient contemplative traditions and more recently formed a step of early cognitive therapy. What ACT adds to this basic distancing is a second step, that of noticing the function of a particular thought or story in a given situation or context. First notice the thought as a thought, next notice what it would make you do in the world. When we are able to perform these two simple steps, we become able to better choose if what our thoughts would make us do is what the person we want to be would do — and if not get a chance to move toward behaving like the person we want to be.

In our work with ACT, we use the hooks metaphor through which we see thoughts and emotions as something that can pull us in unwanted directions. By noticing hooks and what we do next, we can effectively defuse from unhelpful thought patterns by putting into action the two steps of cognitive defusion.

If you are a clinician working with ACT, keeping in mind these two steps will potentiate your practice. The range of defusion exercises is wide: making a practice of saying: “ My / your mind says… ”, using your hands to physicalize thoughts and their distance from your and your client’s head, practicing various thought vocalization exercises (such as repeating thoughts, saying them real fast or real slow, saying them in strange or funny voices). As you use them, remember to ask your clients what that thought or story would make them do in the situations that you are working on and if this is what they would have chosen to do. When your clients notice that it is not what they would have chosen to do had they not bought a particular thought, it helps them identify opportunities for choosing new behaviour.

So as you go through your day, make a practice of noticing your thoughts and emotions and what they would make you do in the situations in which they appear. Gradually, you’ll become more able to notice when your mind produces stories that would seek to narrow your life and your vision of your possibilities. You’ll then be better able to choose who you want to control your life, what truly matters to you, no matter what your monkey mind says.